The clinical territory of osteoporosis management is far more complex than simply prescribing bone density medication; it is a multifaceted discipline where the orthopedic surgeon’s involvement extends significantly beyond the operating theatre. Traditionally, the surgeon is perceived only at the point of failure—when a fragility fracture has already occurred, necessitating immediate and often technically challenging fixation. However, to truly combat the spiraling public health crisis that osteoporosis represents, the orthopedic perspective must be leveraged much earlier in the patient’s journey, transforming the intervention from reactionary trauma care into a proactive cornerstone of skeletal health preservation. The surgeon’s unique vantage point, gained from physically interacting with the compromised bone quality during a procedure, offers invaluable, firsthand insight into the material limitations of the osteoporotic skeleton, which is often difficult to fully appreciate from a mere DEXA scan result alone. This intimate knowledge of bone failure mechanics makes the orthopedic specialist an essential, often underutilized, leader in the long-term care continuum.

The orthopedic surgeon is routinely involved in cases of fragility fractures, and many studies have shown that early osteoporosis screening by the orthopaedic surgeon, as part of the treatment plan, leads to better disease management.

One of the most critical, yet frequently neglected, functions of the orthopedic practice is the systematic identification of patients following an initial fragility fracture. This is a crucial window of opportunity, often referred to as a “sentinel event,” where the patient is already engaged with the healthcare system and demonstrably at high risk for a subsequent, more devastating fracture, such as a hip fracture. The orthopedic surgeon is routinely involved in cases of fragility fractures, and many studies have shown that early osteoporosis screening by the orthopaedic surgeon, as part of the treatment plan, leads to better disease management. Implementing a formal Fracture Liaison Service (FLS) within the orthopedic setting—a concept that has proven remarkably effective in numerous international models—shifts the focus from merely repairing the broken bone to treating the underlying skeletal disease. The surgeon, having witnessed the vulnerability of the bone firsthand, becomes the natural catalyst for initiating diagnostic workups, including appropriate bone mineral density (BMD) testing, and subsequent referral for pharmacological intervention and comprehensive fall risk assessment. Without this deliberate linkage, a startlingly high percentage of patients who experience an osteoporotic break are never actually investigated or treated for their fundamental bone disease, setting the stage for future catastrophic failures.

The hip fracture patient frequently presents with complex comorbidities, including but not limited to impaired hepatic and renal function, diabetes mellitus, dementia, delirium, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and patient polypharmacy.

The actual surgical repair of a fragility fracture, particularly a hip fracture, presents an entirely different set of complex challenges that directly stem from the underlying poor bone quality and the patient’s typical geriatric co-morbidities. Surgeons must select and apply implants and fixation strategies that can secure bone tissue which is inherently weak and prone to fragmentation. Treatment success depends on secure implant fixation as well as on patient-specific factors (fracture stability, bone quality, comorbidity, and gender) and surgeon-related factors (experience, correct reduction, and optimal screw placement). The hip fracture patient frequently presents with complex comorbidities, including but not limited to impaired hepatic and renal function, diabetes mellitus, dementia, delirium, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and patient polypharmacy. These co-existing conditions dramatically escalate the perioperative risk and often dictate a need for a less invasive, more straightforward surgical approach that allows for immediate weight-bearing to facilitate earlier mobilization. Techniques such as cement augmentation for better screw anchorage in low-density bone have increasingly been discussed and adopted to mitigate the risk of mechanical failure in these highly compromised bones, a clear example of surgical innovation driven by the structural demands of osteoporosis.

The local evaluation of each injury has two key facets: the soft tissues and the fracture pattern.

A deep understanding of trauma mechanics and soft tissue injury is equally vital to the orthopedic contribution. In treating fractures in osteoporotic patients, the trauma is often minor—a simple fall from a standing height—but the resulting bony injury is severe due to the deteriorated microarchitecture of the bone. The local evaluation of each injury has two key facets: the soft tissues and the fracture pattern. These two factors, along with the patient’s overall health status, collectively determine the personality of the injury and subsequent decision-making regarding treatment. For instance, an elderly patient with a seemingly simple wrist fracture (Distal Radius) must be approached differently than a young trauma patient. The surgeon must anticipate poorer bone healing potential and the need for more rigid fixation, often involving locking plates, to compensate for the bone’s inability to hold traditional screws under load. This requires a nuanced, individualized approach, moving past standardized fracture management protocols to address the unique biological context of the osteoporotic patient.

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease characterized by a low bone mass and deterioration of bone microarchitecture, leading to bone fragility and an increased risk of fractures.

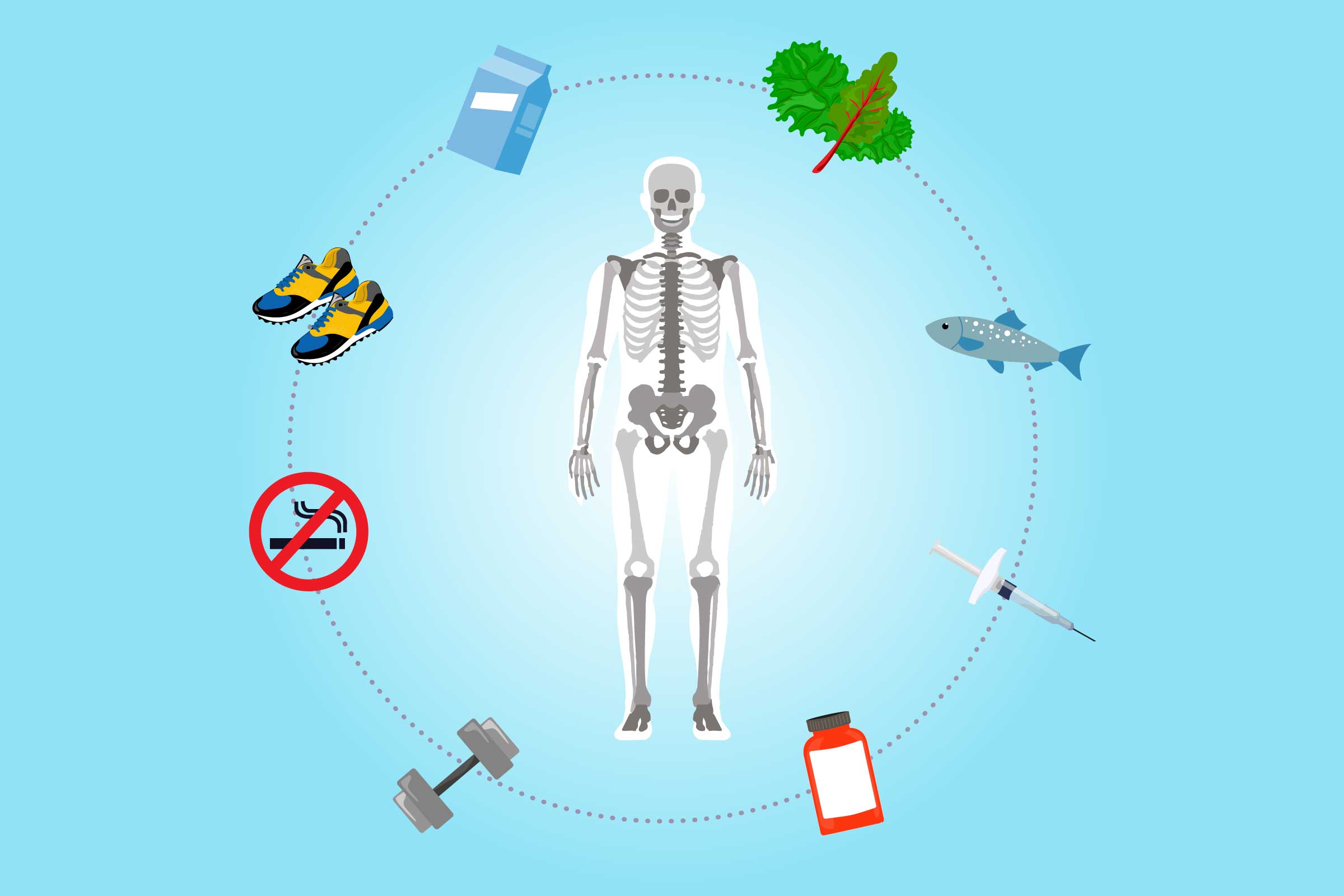

Moving away from the crisis of fracture and back to prevention, the role of the orthopedic team in advocating for proper nutrition and activity is indispensable. Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease characterized by a low bone mass and deterioration of bone microarchitecture, leading to bone fragility and an increased risk of fractures. While many lifestyle recommendations are universally applied, the orthopedic surgeon can tailor advice based on the fracture risk profile and physical limitations observed during examination. Recommendations universally include advising on a diet that incorporates adequate amounts of total calcium intake (1000-1200 mg/day for older adults) and Vitamin D intake (800-1000 IU/day), incorporating supplements if the diet is insufficient. Critically, regular weight-bearing and muscle-strengthening exercise is recommended not just for overall health, but specifically to improve agility, strength, and posture, which directly reduces the risk of falls. The surgeon, in conjunction with a physical therapist, can specifically prescribe exercises—like brisk walking, climbing stairs, or specific resistance training—that safely load the skeleton in a manner that encourages bone strength without risking a new fracture.

Improving postural control is important to reduce the risk of falls.

The necessity of fall prevention cannot be overstated, as the fall is the proximate cause for the vast majority of fragility fractures. The orthopedic guidance here extends beyond the internal skeletal condition to the external environment. Improving muscle strength and balance can also help prevent falls that lead to fractures and disability. Furthermore, physical therapy management often includes specific exercises like Tai chi or Yoga to help improve the individual’s overall physical function and postural control which is important to reduce the risk of falls. The simple, often mundane, details of the home environment must be addressed, such as assessing for slippery surfaces, loose rugs, and tripping hazards like cords or low furniture. The orthopedic follow-up visit, therefore, should ideally incorporate a discussion or a formal checklist regarding home safety assessments and the need for corrective measures, as well as a review of any central nervous system depressant medications that may affect balance. This holistic approach significantly reduces the probability of a recurrence that would necessitate another surgical intervention.

This guidance has been written by a multidisciplinary group of anaesthetists, surgeons and orthogeriatricians to support clinicians in decision making and planning at a difficult time.

The most advanced and effective models of care for this patient population rely on true interdisciplinary collaboration, with the orthopedic surgeon serving as a key player in a much larger team. The management of a patient with a fragility fracture is not a solitary endeavor but requires the combined expertise of multiple specialists. High-quality prompt care of all people with hip and other fragility fractures is a key component of helping with patient outcomes and necessitates a coordinated effort. This includes not only the orthopedic team but also geriatricians (orthogeriatricians), anesthesiologists, rehabilitation specialists, and nurses. The collective goal is to manage the patient’s complex co-morbidities during the perioperative period while simultaneously ensuring timely surgical fixation and the initiation of secondary fracture prevention protocols. For example, specific guidance for the perioperative care of people with fragility fractures is often written by a multidisciplinary group of anaesthetists, surgeons and orthogeriatricians to support clinicians in decision making and planning regarding timing of surgery and choice of anesthesia. This unified front ensures that bone health is managed systemically, not just segmentally.

The orthopaedic surgeon is required to advocate for and occasionally manage patients with osteoporosis and other medical conditions.

Within their outpatient practice, the orthopedic surgeon is required to advocate for and occasionally manage patients with osteoporosis and other medical conditions. This advocacy role is crucial. Given the high rate of non-compliance and the perception among patients that osteoporosis treatment is “optional,” the surgeon’s direct endorsement of a pharmacological plan carries considerable weight. The orthopedic team is often responsible for educating the patient on the severity and risks and harms related to untreated clinical osteoporosis and reinforcing the favorable benefit-to-risk profile for various bone-strengthening treatments. However, this practice is not always consistent, and a gap exists between the recommended screening and intervention rates and actual clinical practice. This variability underscores the ongoing need for continuous education and the implementation of standardized protocols within orthopedic clinics to ensure every fragility fracture is recognized as a medical alert for underlying osteoporosis.

The process and reasoning related to persisting with or stopping OP treatments post-fracture are complex and dynamic.

Patient adherence to long-term osteoporosis medication is notoriously low, creating another significant hurdle that the orthopedic team must help navigate. The process and reasoning related to persisting with or stopping OP treatments post-fracture are complex and dynamic. Many patients re-evaluate the severity and impact of the disease versus the risks and benefits of treatments over time. A patient’s decision to continue or discontinue treatment is often influenced by their perception of the fracture’s severity and their personal understanding of the medication’s role. Surgeons and their staff must therefore engage in ongoing communication that is personalized, not generic. This involves discussing specific medication options, such as bisphosphonates or anabolic agents, in the context of the patient’s fracture history and their individual tolerance, helping them to transition their mindset from short-term recovery to long-term disease management. The perceived necessity of the drug is often the deciding factor in persistence.

Various factors, such as patient age, comorbidities, activity level, age of the fracture or pre-injury arthrosis, and experience of the surgeon influence the decision-making for fixation.

Even the selection of the correct surgical implant in an osteoporotic bone is far from a trivial matter, demanding a calculation that balances mechanical stability against biological invasiveness. Various factors, such as patient age, comorbidities, activity level, age of the fracture or pre-injury arthrosis, and experience of the surgeon influence the decision-making for fixation. The choice between different methods—ranging from simple pinning to complex total joint replacement—is heavily influenced by the patient’s remaining expected functional demand and the inherent poor bone quality. For example, in a severely osteoporotic hip, a surgeon may lean towards a hemiarthroplasty over internal fixation due to the high risk of fixation failure in a bone that offers insufficient purchase for screws. The goal is always to provide an immediate, stable construct that minimizes reoperation risk, allowing the patient to return to safe mobilization as quickly as possible, thus mitigating the cascade of complications associated with prolonged immobility in the elderly.

Investigate any broken bone in adulthood as suspicious for osteoporosis, regardless of cause.

Finally, the key shift in orthopedic thinking requires a cultural change: viewing any fracture in an adult over a certain age through the lens of bone health. The clinical guidance is clear: Investigate any broken bone in adulthood as suspicious for osteoporosis, regardless of cause. This proactive diagnostic imperative transforms the orthopedic clinic into a crucial screening center. Beyond addressing the acute injury, the surgeon’s team must routinely perform BMD testing in appropriate demographic groups (e.g., women ≥ 65 years and men ≥ 70 years) and annually measure height to detect signs of vertebral compression. This is how the specialty moves from simply fixing broken parts to holistically managing the systemic disease that caused the breakage, ultimately saving the patient from the cascading physical and psychological toll of recurrent fragility fractures and maintaining functional independence.